T'ai chi ch'uan

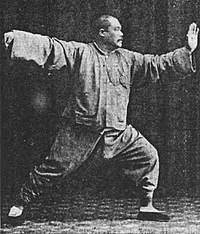

Yang Chengfu in a posture from the Yang-style t'ai chi ch'uan solo form known as Single Whip c. 1931 | |

| Also known as | t'ai chi ch'üan; taijiquan |

|---|---|

| Focus | Hybrid |

| Hardness | Forms competition, light-contact (pushing hands, no strikes), full contact (striking, kicking, throws, etc.) |

| Country of origin | |

| Creator | Said to be Zhang Sanfeng |

| Famous practitioners | Chen Wangting, Chen Changxing, Yang Lu-ch'an, Wu Yu-hsiang, Wu Ch'uan-yu, Wu Chien-ch'uan, Sun Lu-t'ang, Yang Chengfu, Chen Fake, Wang Pei-sheng, |

| Parenthood | Tao Yin |

| Olympic sport | Demonstration only |

| T'ai chi ch'uan (Taijiquan) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 太極拳 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 太极拳 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | supreme ultimate fist | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of the series on Chinese martial arts |

|

| List of Chinese martial arts |

|---|

| Terms |

| Historical places |

|

| Historical people |

|

| Famous modern actors |

|

| Legendary figures |

|

| Related |

T'ai chi ch'uan (simplified Chinese: 太极拳; traditional Chinese: 太極拳; pinyin: tàijíquán; Wade–Giles: t'ai chi ch'üan; literally "Supreme Ultimate Fist"), often shortened to T'ai chi or Tai chi in the West, is a type of internal Chinese martial art practiced for both its defense training and its health benefits. It is also typically practiced for a variety of other personal reasons: its hard and soft martial art technique, demonstration competitions, and longevity. As a consequence, a multitude of training forms exist, both traditional and modern, which correspond to those aims. Some of t'ai chi ch'uan's training forms are especially known for being practiced at what most people categorize as slow movement.

Today, t'ai chi ch'uan has spread worldwide. Most modern styles of t'ai chi ch'uan trace their development to at least one of the five traditional schools: Chen, Yang, Wu/Hao, Wu, and Sun.

Overview

The term t'ai chi ch'uan translates as "supreme ultimate fist", "boundless fist", "great extremes boxing", or simply "the ultimate" (note that chi in this instance is the Wade-Giles transliteration of the Pinyin jí, and is distinct from qì (or chi 氣), meaning "life energy". The concept of the Taiji ("supreme ultimate") appears in both Taoist and Confucian Chinese philosophy, where it represents the fusion or mother of Yin and Yang into a single Ultimate, represented by the Taijitu symbol. T'ai chi theory and practice evolved in agreement with many Chinese philosophical principles, including those of Taoism and Confucianism.

T'ai chi training involves five elements, nei gung, tui shou (response drills), sanshou (self defence techniques), weapons, and solo hand routines, known as forms (套路 taolu). While the image of t'ai chi ch'uan in popular culture is typified by exceedingly slow movement, many t'ai chi styles (including the three most popular - Yang, Wu, and Chen) - have secondary forms of a faster pace. Some traditional schools of t'ai chi teach partner exercises known as "pushing hands", and martial applications of the forms' postures.

In China, t'ai chi ch'uan is categorized under the Wudang grouping of Chinese martial arts—that is, the arts applied with internal power (an even broader term encompassing all internal martial arts is Neijia) Although the Wudang name falsely suggests these arts originated at the so-called Wudang Mountain, it is simply used to distinguish the skills, theories and applications of the "internal arts" from those of the Shaolin grouping, the "hard" or "external" martial art styles.

Since the first widespread promotion of t'ai chi's health benefits by Yang Shaohou, Yang Chengfu, Wu Chien-ch'uan, and Sun Lutang in the early 20th century, it has developed a worldwide following among people with little or no interest in martial training, for its benefit to health and health maintenance. Medical studies of t'ai chi support its effectiveness as an alternative exercise and a form of martial arts therapy.

Master Choy Hok Pang, a disciple of Yang Ching Po and the first proponent of T'ai Chi Ch'uan to teach in the United States, began teaching T'ai Chi Chuan in the United States in 1939. Subsequently, his son and student Master Choy Kam Man emigrated to San Francisco from Hong Kong in 1949 to teach T'ai Chi Ch'uan in San Francisco's Chinatown. Choy Kam Man taught until he died in 1994.

It is purported that focusing the mind solely on the movements of the form helps to bring about a state of mental calm and clarity. Besides general health benefits and stress management attributed to t'ai chi training, aspects of traditional Chinese medicine are taught to advanced t'ai chi students in some traditional schools.

Some martial arts, especially the Japanese martial arts, require students to wear a uniform during practice. In general, t'ai chi ch'uan schools do not require a uniform, but both traditional and modern teachers often advocate loose, comfortable clothing and flat-soled shoes.

The physical techniques of t'ai chi ch'uan are described in the tai chi classics, a set of writings by traditional masters, as being characterized by the use of leverage through the joints based on coordination and relaxation, rather than muscular tension, in order to neutralize, yield, or initiate attacks. The slow, repetitive work involved in the process of learning how that leverage is generated gently and measurably increases, opens the internal circulation (breath, body heat, blood, lymph, peristalsis, etc.)

The study of t'ai chi ch'uan primarily involves three aspects:

Name

What is now known as "T'ai chi ch'uan" only appears to have received this appellation from around the mid 1800's. There was a scholar in the Imperial Court by the name of Ong Tong He who witnessed a demonstration by Yang Luchan ("Unbeatable Yang"). Afterwards Ong wrote: "Hands holding Taiji shakes the whole world, a chest containing ultimate skill defeats a gathering of heroes." This was the time when Yang Luchan made the Chen clan's martial art known to the world through his own form ("Yang family style").

Before this time the Art had no name. It was simply an unusual martial art practiced by a few. Jiang Fa passed down the Art to Chen Qing Ping in Zhao Bao Town and Chen Zhang Xin in Chen Jia Gou. Before the time of Yang Luchan, the Art appears to have been generically described by outsiders as "Touch Boxing" (沾拳 zhan quan), "Soft Boxing" (绵拳 mian quan) or "The Thirteen techniques" (十三式 shi san shi).

The name "T'ai chi ch'uan" is held to be derived from the Taiji symbol (Taijitu or T'ai chi t'u, 太極圖), commonly known in the West as the "yin-yang" diagram.

The appropriateness of this more recent appellation is seen in the oldest literature preserved by these schools where the art is said to be a study of yin (receptive) and yang (active) principles, using terminology found in the Chinese classics, especially the I Ching and the Tao Te Ching.

History and styles

Family trees

Legendary figures

| Zhang Sanfeng* c. 12th century NEIJIA | |||||||

| | | | | | |||

| Wang Zongyue* 1733-1795 | |||||||

Five major classical family styles

| Chen Wangting 1580–1660 9th generation Chen CHEN STYLE | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | | | | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | ||||||||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chen Changxing 1771–1853 14th generation Chen Chen Old Frame | | | | | | | | | | | | | | Chen Youben c. 1800s 14th generation Chen Chen New Frame | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | ||||||||||||||||||

| Yang Lu-ch'an 1799–1872 YANG STYLE | | | | | | | | | | | | | | Chen Qingping 1795–1868 Chen Small Frame, Zhaobao Frame | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | ||||||||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yang Pan-hou 1837–1892 Yang Small Frame | | | | | | Yang Chien-hou 1839–1917 | | | | | | Wu Yu-hsiang 1812–1880 WU/HAO STYLE | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |||||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wu Ch'uan-yu 1834–1902 | | Wang Jaio-Yu 1836-1939 Original Yang | | Yang Shao-hou 1862–1930 Yang Small Frame | | Yang Chengfu 1883–1936 Yang Big Frame | | 1832–1892 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | ||||||||||||||||

| Wu Chien-ch'uan 1870–1942 WU STYLE 108 Form | | Kuo Lien Ying 1895–1984 | | | | | | Yang Shou-chung 1910–85 | | Hao Wei-chen 1849–1920 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | ||||||||||||||||||

| Wu Kung-i 1900–1970 | | | | | | | | | | | | | | Sun Lu-t'ang 1861–1932 SUN STYLE | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | ||||||||||||||||||

| Wu Ta-k'uei 1923–1972 | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 1891–1929 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Modern forms

| Yang Chengfu | |||||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | | ||||||

| | | | | | |||||||||||

| Cheng Man-ch'ing 1901–1975 Short (37) Form | | Chinese Sports Commission 1956 Beijing 24 Form | |||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | |||||||

| | | | | 1989 42 Competition Form (Wushu competition form combined from Sun, Wu, Chen, and Yang styles) | |||||||||||

Training and techniques

Modern T'ai chi

T'ai chi as sport

In order to standardize t'ai chi ch'uan for wushu tournament judging, and because many t'ai chi ch'uan teachers had either moved out of China or had been forced to stop teaching after the Communist regime was established in 1949, the government sponsored the Chinese Sports Committee, who brought together four of their wushu teachers to truncate the Yang family hand form to 24 postures in 1956. They wanted to retain the look of t'ai chi ch'uan but create a routine that would be less difficult to teach and much less difficult to learn than longer (in general, 88 to 108 posture), classical, solo hand forms. In 1976, they developed a slightly longer form also for the purposes of demonstration that still would not involve the complete memory, balance, and coordination requirements of the traditional forms. This became the Combined 48 Forms that were created by three wushu coaches, headed by Professor . The combined forms were created based on simplifying and combining some features of the classical forms from four of the original styles: Chen, Yang, Wu, and Sun. As t'ai chi again became popular on the mainland, more competitive forms were developed to be completed within a six-minute time limit. In the late-1980s, the Chinese Sports Committee standardized many different competition forms. They developed sets to represent the four major styles as well as combined forms. These five sets of forms were created by different teams, and later approved by a committee of wushu coaches in China. All sets of forms thus created were named after their style, e.g., the Chen-style National Competition Form is the 56 Forms, and so on. The combined forms are The 42-Form or simply the Competition Form. Another modern form is the , created in the 1950s; it contains characteristics of the Yang, Wu, Sun, Chen, and Fu styles blended into a combined form. The wushu coach Bow Sim Mark is a notable exponent of the 67 Combined form.

These modern versions of t'ai chi ch'uan (often listed as the pinyin romanization Taijiquan among practitioners, teachers and masters) have since become an integral part of international wushu tournament competition, and have been featured in popular movies starring or choreographed by well-known wushu competitors, such as Jet Li and Donnie Yen.

In the 11th Asian Games of 1990, wushu was included as an item for competition for the first time with the 42-Form being chosen to represent t'ai chi. The International Wushu Federation (IWUF) applied for wushu to be part of the Olympic games, but will not count medals.

Practitioners also test their practical martial skills against students from other schools and martial arts styles in pushing hands and sanshou competition.

Qigong vs T'ai chi

Health benefits

Before t'ai chi's introduction to Western students, the health benefits of t'ai chi ch'uan were largely explained through the lens of traditional Chinese medicine, which is based on a view of the body and healing mechanisms not always studied or supported by modern science. Today, t'ai chi is in the process of being subjected to rigorous scientific studies in the West. Now that the majority of health studies have displayed a tangible benefit in some areas to the practice of t'ai chi, health professionals have called for more in-depth studies to determine mitigating factors such as the most beneficial style, suggested duration of practice to show the best results, and whether t'ai chi is as effective as other forms of exercise.

Chronic conditions

Researchers have found that intensive t'ai chi practice shows some favorable effects on the promotion of balance control, flexibility, cardiovascular fitness, and has shown to reduce the risk of falls in both healthy elderly patients, and those recovering from chronic stroke, heart failure, high blood pressure, heart attacks, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's, Alzheimer's and fibromyalgia,. T'ai chi's gentle, low impact movements burn more calories than surfing and nearly as many as downhill skiing.

T'ai chi, along with yoga, has reduced levels of LDLs 20–26 milligrams when practiced for 12–14 weeks. A thorough review of most of these studies showed limitations or biases that made it difficult to draw firm conclusions on the benefits of t'ai chi. A later study led by the same researchers conducting the review found that t'ai chi (compared to regular stretching) showed the ability to greatly reduce pain and improve overall physical and mental health in people over 60 with severe osteoarthritis of the knee. In addition, a pilot study, which has not been published in a peer-reviewed medical journal, has found preliminary evidence that t'ai chi and related qigong may reduce the severity of diabetes. In a randomized trial of 66 patients with fibromyalgia, the t'ai chi intervention group did significantly better in terms of pain, fatigue, sleeplessness and depression than a comparable group given stretching exercises and wellness education.

A recent study evaluated the effects of two types of behavioral intervention, t'ai chi and health education, on healthy adults, who, after 16 weeks of the intervention, were vaccinated with VARIVAX, a live attenuated Oka/Merck Varicella zoster virus vaccine. The t'ai chi group showed higher and more significant levels of cell-mediated immunity to varicella zoster virus than the control group that received only health education. It appears that t'ai chi augments resting levels of varicella zoster virus-specific cell-mediated immunity and boosts the efficacy of the varicella vaccine. T'ai chi alone does not lessen the effects or probability of a shingles attack, but it does improve the effects of the varicella zoster virus vaccine.

Stress and mental health

A systematic review and meta-analysis, funded in part by the U.S. government, of the current (as of 2010) studies on the effects of practicing t'ai chi found that, "Twenty-one of 33 randomized and nonrandomized trials reported that 1 hour to 1 year of regular t'ai chi significantly increased psychological well-being including reduction of stress, anxiety, and depression, and enhanced mood in community-dwelling healthy participants and in patients with chronic conditions. Seven observational studies with relatively large sample sizes reinforced the beneficial association between t'ai chi practice and psychological health."

There have also been indications that t'ai chi might have some effect on noradrenaline and cortisol production with an effect on mood and heart rate. However, the effect may be no different than those derived from other types of physical exercise. In one study, t'ai chi has also been shown to reduce the symptoms of Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in 13 adolescents. The improvement in symptoms seem to persist after the t'ai chi sessions were terminated.

In June, 2007 the United States National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine published an independent, peer-reviewed, meta-analysis of the state of meditation research, conducted by researchers at the University of Alberta Evidence-based Practice Center. The report reviewed 813 studies (88 involving t'ai chi) of five broad categories of meditation: mantra meditation, mindfulness meditation, yoga, t'ai chi, and qigong. The report concluded that "the therapeutic effects of meditation practices cannot be established based on the current literature," and "firm conclusions on the effects of meditation practices in healthcare cannot be drawn based on the available evidence.

Tai chi chuan's fighting effectiveness

One of the most recurrent and controversial topics among tai chi chuan practitioners is which of the various tai chi chuan styles is the most effective one in fighting. The discussion is usually topicalised around Chen and Yang styles, as the oldest and most widely practised styles nowadays. It is generally acknowledged that Chen's proponents argue in favour of their style, not least because the rigorous and explosive way that the Chen forms are to be done makes the link between their moves and their potential fighting applications much more directly and clearly extrapolated than what is the case in the other styles.

Yang style practitioners seem to reply that their forms are not propounded but slow and relaxed for the only reason that done this way it is more beneficial when learning how to get used to all what has to be collectively orchestrated, such as the correct posture, the appropriate breathing, the seamless transitions, etc, aspects on the mastery of which one can be working indefinitely indeed. In addition, Yang practitioners bring in favour of their argument the alleged victory of Yang Lu Chan, the founder of Yang style tai chi chuan, over a martial artist who had fought and won all the senior members of the Chen village (Chenjiagou) and who was insisting on also fighting Chen Chang Xing, the head of the Chen village, although Chen Chang Xing never accepted the challenge perhaps for fear of losing all the more so because he was too old back then or for any other reason that we cannot know nowadays.

In any case, all the tai chi chuan styles seem to join forces when they have to argue for the effectiveness of tai chi chuan in general. Tai chi chuan's effectiveness is nowadays sometimes not acknowledged for a variety of reasons. One of these reasons is some people's difficulty to see any fighting elements in tai chi chuan. A lot of instructors are ignorant of what tai chi chuan really is, but they continue teaching it taking advantage of the fact that the legislation in their countries allows them to do so since there is not any one overseeing official international body or an individual keeper to ratify instructors and their knowledge and skills. Then, as is the case in acupuncture, homeopathy, astrology, palmistry, and other disciplines of the 'alternative scene', there are many self-appointed gurus, whose sessions give zero if not negative results and should be avoided.

Or the so-called 'walking meditation' and the health benefits thereof are obfuscated, especially when it comes to Yang tai chi chuan, minimasing or even negating the fighting focus. The parody films with tai chi chuan masters flying around or having supernatural strength or speed or reflectives do not help either (see section Tai Chi Chuan in Popular Culture below), and that is also the case with the modern sport-oriented point-gathering standardised or creative tai chi chuan forms (taolu) such the ones of the modern wushu competitions. All these spread tai chi chuan, but also perpetuate the vicious circle of ignorance about tai chi chuan's fighting elements.

Others acknowledge the fighting elements of tai chi chuan, but they argue that these are not effective enough. One could counter-argue this by referring them to the hard facts that tai chi chuan has been used even in real life battlefields from its inception in the 13th century and throughout China's history ever since, and has thus proven its real nature. Lately, in its 37 move form version shortened by , it also became the martial art taught to the Chinese People’s Liberation Army during World War II. Also, it is worth referring to the tai chi chuan classic texts known as tai chi chuan classics, e.g. Yang Ban Hou's Forty Tai Chi Chuan Treatises, in which there are extensive discussions about the inclusion of striking with the hands, the elbows, the shoulders, the knees, kicking with the feet, air chokings, blood blockings, muscle tearings, bone breakings and joint misplacements or joint locks (chin na), maximising effect by aiming at specific vulnerable points (), wrestling throw aways and take downs (shuai jiao), specific advice of how all these should be executed and when they should be executed in fighting, as well as how to deal with the opponents' upcoming attacks using what later came to be known as pushing hands (tui shou), how to draw from your internal resources too with this putting tai chi chuan in the so-called 'internal' martial arts (neijia), and many more.

It is then transpired that tai chi chuan is not only fight-related but also that its syllabus is a well-rounded one. It is on these premises that the famous martial arts author and monk Wong Kiew Kit, fourth generation successor from the , although he himself teaches shaolin gong fu styles and not tai chi chuan, and perhaps this adds to the objectivity of his words, in his Complete Book of Tai Chi Chuan (2001: pp. 1–2), he writes:

Tai chi chuan in popular culture

Tai chi chuan plays an important role in many martial arts and fighting action movies, series, novels, especially in those ones which belong to the wuxia genre, as well as in video games, trading cards games, etc. Fictional portrayals often refer to Zhang San Feng, who is reported to be the first one harnessing and operationalising the benefits of the 'internal' and the 'soft', and to the Taoist monasteries of Wudang Mountains, where he lived.

Movies

Series

Games

Books

See also

Notes

References and Further reading

- Choy, Kam Man (1985-05-05). Tai Chi Chuan. San Francisco, California: Memorial Edition 1994.

- Logan, Logan (1970). Ting: The Caldron, Chinese Art and Identity in San Francisco. San Francisco, California: Glide Urban Center.

- Davis, Barbara (2004). Taijiquan Classics: An Annotated Translation. North Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1556434310.

- Eberhard, Wolfram (1986). A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols: Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London. ISBN 0415002281.

- Jou, Tsung-Hwa (1998). Tao of Tai Chi Chuan, 3rd ed.. Tuttle. ISBN 978-0804813570.

- T'ai Chi Magazine bimonthly. Wayfarer Publications. 2008. ISSN 0730-1049. http://www.tai-chi.com.

- Taijiquan Journal. Taijiquan Journal. 2008. ISSN 1528-6290. http://www.taijiquanjournal.com.

- Wile, Douglas (1983). Tai Chi Touchstones: Yang Family Secret Transmissions. Sweet Ch'i Press. ISBN 978-0912059013.

- Yang, Yang (2008). Taijiquan: The Art of Nurturing, The Science of Power. Zhenwu Publication; 2nd edition. ISBN 978-0974099019.

External links

- "Medical Research on T'ai Chi & Qigong (Chi Kung)". World Tai Chi Day. http://www.worldtaichiday.org/WTCQDHlthBenft.html. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- "Tai Chi Boosts Immunity, Improves Physical Health in Seniors". Acupuncture Today 04 (11). 2003. http://www.acupuncturetoday.com/archives2003/nov/11taichi.html. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- "Tai Chi: With slow movements as fluid as silk, the gentle Chinese practice of Tai Chi seems tailor-made for easing sore joints and muscles". Arthritis Today. http://ww2.arthritis.org/resources/arthritistoday/2000_archives/2000_07_08_taichi.asp. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- "World T'ai Chi & Qigong Day's Headline News". World Tai Chi Day. http://www.worldtaichiday.org/HeadlineNews.html. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- "Kung Fu Fitness Association". http://www.kungfufitness.co.uk.

- "Tai Chi World". http://www.taijiworld.com.

- Videos of the major styles

- Yang Zhenduo's Yang style at YouTube

- Wu Yinghua's Wu Jianquan style

- Chen Shitong's Chen style at Google Video

- Sun Jianyun's Sun style

- Hao Shaoru's Wu/Hao style

- 24-form Beijing form

- 108-form Yang Tai Chi Chuan

- Wu (Hao) Tai Chi Online Study

Retrieved from : http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=T%27ai_chi_ch%27uan&oldid=465959769

No comments:

Post a Comment